Saturday, 14 May 2016

To All The Kids Who Think They're Not Good Enough For University (And The Teachers Who Agree)

Tuesday, 25 November 2014

My Great-Grandfather and the Peaky Blinders

At the age of six I asked my mum for piano lessons and my parents were unsure where this aspiration had come from since most of my family were musically illiterate and had expressed no interest whatsoever in playing a musical instrument. Four years and many piano lessons later, I overhead my father mention in conversation with a neighbour that my great-grandfather James Aloysious (known as Curly) was very musical and he played the piano and the mandolin. When I asked my father about James he told me how my aunt would sit on James’s lap at the piano and put her tiny hands over his large hands while he played the keys. He mentioned how James's hands were rough and his knuckles were beaten up from the fights.

I thought that was an odd thing to say, ‘from the fights’.

My father showed me a photograph of my great-grandfather in his later years and I was surprised to see that James was the absolute spitting image of my father and, in turn, of me. I felt a close connection with James and pestered my father to tell me more about James’s life. And the more that I discovered about him, the more I found him to be a fascinating individual.

James lived in Harborne, he was ex-army and a bare knuckle fighter at Smethwick market. Every Sunday morning he would walk from Harborne to Smethwick to fight and when he returned home he would give his wife Florie all the silver from the win money that he had earned and he kept the copper for himself as beer money. He seemed to make a fair living out of it. James and his family were well looked after because they were in with 'the right crowd' and knew 'the right people', although the company that James kept seemed very dubious indeed. A number of shady characters cropped up at various points in my father’s stories, such as the mysterious Italian Mr Mansini who found my grandfather a job when he came out of the army. Mr Mansini sent my grandfather to the local factory with a note simply saying that he had been sent by Mr Mansini - the note alone was a guarantee of a job and the gesture was made because my grandfather was Curly’s son and ‘Curly and his family were to be well looked after’.

But the most memorable – and disturbing - thing that my father told me about James was this; if James went out for the day with his family then he would wear his ‘home cap’, but if he went out of the house on an evening wearing his ‘working cap’ then my great-grandmother would stay awake and wait up all night in the front bay window of the house until he came home. She would stay up and wait for him because if James went out wearing his working cap then she knew there was going to be trouble. When I asked about the significance of the caps, my father explained that the working cap had razor blades sewn in the rim which came in handy if there was ever a fight. And, by the sounds of it, there were lots of fights. James played the mandolin in the Green Man pub in Harborne and one evening there was a huge fight between his group of friends and the police. It seemed to have been some kind of sting operation targeting them all. James took out three policemen, he smashed his mandolin over the head of one policeman (thereby ending his musical career) and he threw another policeman through the front window of the pub into the horse road outside. The police took James to Steel House Lane police station where he 'fell down the steps of the police station' (he was beaten up) and my great-grandmother claimed that he was never the same again afterwards.

|

| Note on the back of a photo of my great-grandfather |

I remember this conversation well because I was not only shocked by the thought of slashing someone's face with razor blades (I must have been about 10yrs old at the time!), but also by the way in which my father spoke so matter-of-factly about it all and with such an oddly warm affection towards the men in the stories. I had heard both my father and my grandfather mention the words ‘peaky blinder’ before and I didn’t know, or much care at the time, who they were referring to. But now it all made sense. My father and grandfather spoke kindly about James and his friends because these individuals had ‘principals’ - they had a strong family-like bond, they would watch out for one another and their families and they were firmly ‘on our side’. I took comfort in knowing that, due to my surname, I would have nothing to fear had I encountered one of these suspicious characters on the street.

|

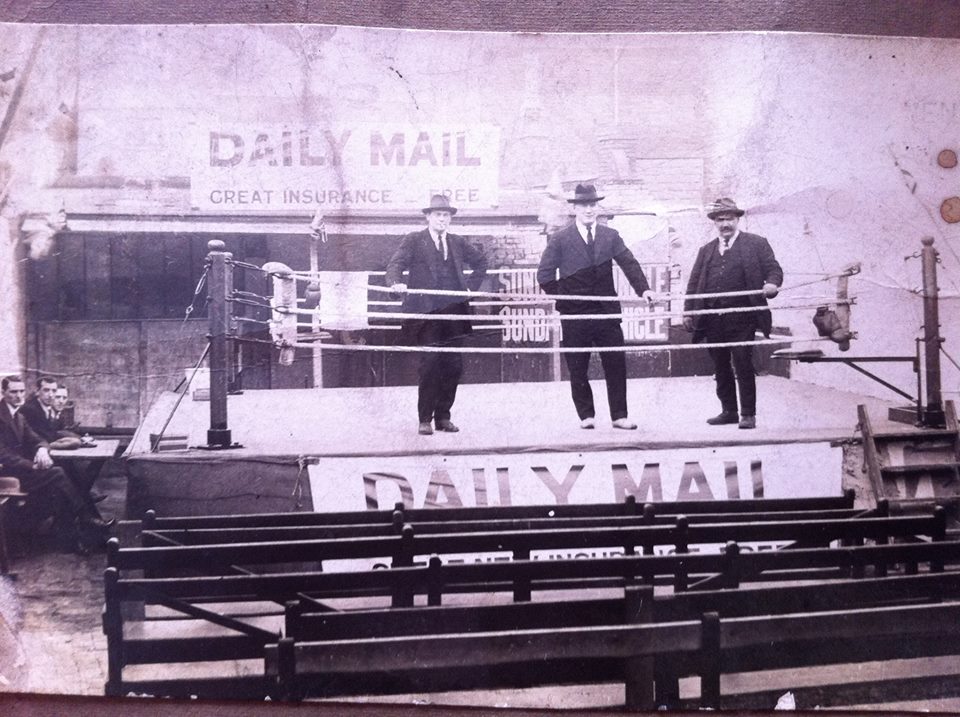

| Sam (left) and business associates |

My mother recalls that the words ‘peaky blinders’ were banded around the household when she was a child and she was aware that Sam mixed equally with both well-heeled individuals and shady groups who protected his business. The Curlys of the world were on Sam’s payroll rather than his drinking buddy in the pub - in fact it became a running joke in my household that my father’s family were on the rough-and-ready, 'practical' side of the Birmingham gangs, whereas my mother’s family were much more discreet with their dealings and ‘higher up the food chain’!

|

| Sam Richards (centre) and his boxing ring |

I remember vividly the stories

that my grandparents told me about Birmingham in that era and I have

portraits and photographs of James and Sam and assorted paraphernalia from

their lives. Most of all I remember the houses, the smell of old wood and

tobacco, the strange turns of phrase when they spoke, the way that humour

intertwined with violence and the physicality of close friendships. I remember

visiting my great-aunt who lived to be over one-hundred years old and seeing

how she kept her old terraced house perfectly-preserved, with a rocking chair

in front of an open fire, lace antimacassars on the armchairs and a

freezing cold outside toilet. I remember my godfather Luigi and how friends

would laugh at the idea of having an Italian godfather looking out for me. I

remember the large men that regularly visited my grandad’s house, how well

dressed and friendly they were yet so big and scary. How one of them would

squeeze my knees to make me laugh every time he visited. It would really hurt and I could never wriggle away from him, but he made me laugh so much and he was always extremely polite to the women of the house.

But, aside from modernising our houses, things haven’t changed a great deal in some areas of Birmingham. I grew up on an estate in Birmingham not far from where Curly and Sam lived. It could be a violent place but the locals valued strong generational links forged between large, influential families that looked out for each other. Loyalty and family names still carry a great deal of weight around here and your reputation follows you around. I’ve worked in funeral parlours and mental asylums, swanned around masonic halls in ballgowns, listened to security experts lecture me on the latest developments in bio weaponry, held the keys to churches and gin bars, dated spies and had partners bring undercover police along to romantic nights out in case I wasn’t the friendly gal I promised to be. Sometimes your history can be both a blessing and a curse. One day I might be inclined to write about it all, maybe when I've finished living it...

|

| A 19thC Small Heath pub token, use to pay for drinks and for groups to recompense the landlord for the use of recreational facilities and back rooms for group meetings |

|

| Sick Society token, entitling the bearer to financial support to see a doctor or help with burial costs for himself, wife or child |

But the greatest accomplishment of Peaky Blinders is that it portrays the central characters as both hero and villain thereby giving the viewer the uneasy experience of both fearing and admiring them, which was the exact same uncomfortable feeling that I grappled with upon learning about my family connections with the blinders as a child. James’s working cap gave me more than a few nightmares as a child, but there are aspects of his personality and values that I admire and I see within myself these days. Perhaps the fondness that I have for James, Sam and their friends is borne out of a realisation that although they were violent men who sailed on the wrong side of the law, they also had strong family values, they were loyal to those who were loyal to them and they would protect their friends and loved ones at all costs – all values that our modern-day society would do well to aspire to.

(Interestingly, my auntie tells me that James’s death was quite a talking point. The story goes that a gypsy came into the Green Man pub in Harbourne and started reading palms. James paid her to read his palm, she took one look at his hand and refused, then left the pub straight away. James died only days afterwards).

Helen Ingram (@drhingram)